Insurance regulator IRDAI recently scrapped the entry age for health insurance. While the move doesn’t mean the age cap of 65 for buying health insurance has been removed, as most news reports claimed, it means the regulator has given the insurers the right to set any entry-age limit in the product they design.

But will this policy change, effective from April 1, will help remove the complexities of health insurance? If you go by the textbook definition, insurance compensates for risks such as loss of income due to the death of an earning member in working age and huge hospital bills.

Let us take the example of 100 persons, each aged 30 taking a term life insurance policy of Rs 1 crore for up to 60 years. Suppose five persons out of these 100 die during the policy term. Then insurer has to pay a total of Rs 5 crore and if they manage to collect Rs 5 crore, it breaks even. The amount will be Rs 5 crore if each of the 95 survivors pays Rs 5.27 lakh. And they need to pay this much only over the policy period of 30 years, equivalent to an annual premium of Rs 17,544 (premium will go up to cover the expenses and profit of the insurer, but it will soften as those 5 dying too will have paid one or more annual premiums). Thus heirs of even the person dying the day before turning 60 and paying all the 30 annual premiums get a payout of Rs 1 crore, which is 19 times the premium paid – not a bad deal.

In this example, even though the probability of early death among these 30-year-olds is a low 5 per cent, not one of them knows who among them will be the unfortunate five. That is low probability and high uncertainty. Insurance, of any kind is viable as long as this principle holds. When this principle holds, claim payouts will be less than the premium received and the insurer remains solvent.

Now imagine the same hundred 30-year-olds taking health insurance for up to 70 years. What is the maximum amount payable by an insurer on a policy? It is given by multiplying the sum assured by the number of claims. Unlike life policy where the maximum number of claims is one, the sum assured in a health policy is payable on an annual basis – with a health cover of Rs 5 lakhs, if you incur Rs 5 lakhs hospitalisation expense in a particular year, you are paid that much. If hospitalisation is required in the next year also, the insurer has to pay the claim again.

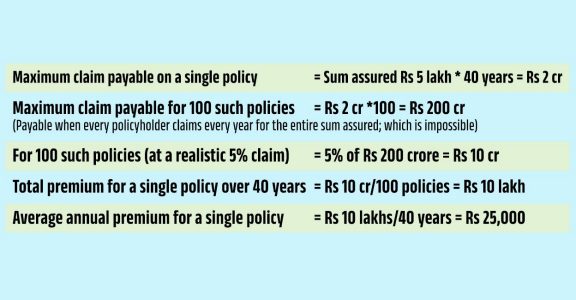

In our example, the math goes like this:

Maximum claim payable on a single policy = Sum assured Rs 5 lakh * 40 years = Rs 2 crores

Maximum claim payable for 100 such policies = Rs 2 crore *100 = Rs 200 crores (Payable when every policyholder claims every year for the entire sum assured; which is impossible)

For 100 such policies (at a realistic 5% claim) = 5% of Rs 200 crore = Rs 10 crore

Total premium for a single policy over 40 years = Rs 10 crore/100 policies = Rs 10 lakh

Average annual premium for a single policy = Rs 10 lakhs/40 years = Rs 25,000

Thus at the very same 5 per cent probability, to the insurer, a health cover of Rs 5 lakh for 40 years is twice the liability of a term life cover of Rs 1 crore for 30 years! For the insured too, the premium burden is higher for the health policy. And the average annual premium of Rs 25,000 shown above hides a lot – the premium for a 30-year-old will be way below the average whereas for a 60-year-old, it will be a few times the average. Fixed annual premiums are a feature of life policies alone. Moreover, this calculation assumes zero inflation in healthcare costs, which is unrealistic. When the medical inflation rate is higher than the income growth rate of policy policyholder, premium payment can turn burdensome as the sum assured has to go up.

Now let us consider a pool of one hundred 60-year-olds taking new health policies. The probability of claims for such a pool is high, say 20 per cent. In other words, high probability and hence low uncertainty. It violates the low probability and high uncertainty principle we saw earlier and makes insurance unviable. The insurer goes broke by underwriting such a pool of risk by taking reasonable premiums. But he can increase premiums so that all claims are paid – but such high premiums make it unattractive for the customers.

At 20 per cent probability, one out of five 60-year-olds incur hospitalisation expenses. Thus premium from five people is claimed by one of them. Hence for a cover of Rs 5 lakh, the insurance company needs to collect a premium of Rs 1 lakh. So someone paying a premium for four years pays Rs 4 lakh and when he pays the fifth year premium, the sum assured equals the premium paid. No claim in the first 4 years and a full claim in the 5th year means you are simply getting back only what you’ve paid – a really bad deal

Complications do not end here. An insurer has to pay a claim after ascertaining the happening of the claim event during the policy term. A life insurer has to ascertain only death and there is no dispute as to the amount to be paid, which is the entire sum assured. All neat. But a health insurer? Hospital first diagnoses and then treats. The cost of this is paid by the insurer subject to the cap of sum assured. An insurer may not dispute the disease diagnosed but may claim that some of the expensive diagnostic tests were needless. The same dispute may be raised for treatment procedures done resulting in a substantial reduction in payout

Insurance works in case of unexpected events and negative surprises. A 30-year-old contracting a serious illness is unexpected and a negative surprise. But a 70-year-old contracting the same disease is not so unexpected and not much of a surprise. For the high healthcare expenditure of the elderly, health insurance seems to be of questionable efficiency.

(The writer is an ex-banker and currently teaches economics & finance.)